It’s brought celebrity, swag, people and cash.

In 25 years, the $67.4 million Monona Terrace — the most controversial building project in city history — sealed the city’s ties to renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright, energized a listless Downtown, and pumped $697.5 million from conventions and conferences into the local economy.

The rare triple-use building — convention center, tourist attraction and community gathering spot — Monona Terrace has hosted the U.S. Conference of Mayors, Ironman Wisconsin, the World Championship Cheese Contest, National Public Radio’s “Whad’ Ya Know?” the Dane County Farmers’ Market, community programs, and rooftop concerts.

The Monona Terrace Community and Convention Center, a catalyst for the revitalization of Downtown Madison, turns 25 this month. A celebration is set for next Saturday.

Runners, walkers and cyclists heavily use the center’s waterfront path, and its retaining wall quickly became a hot fishing spot.

People are also reading…

“Events at Monona Terrace connect some of the brightest minds to advance important work and research, and millions of people from all walks of life have gathered and celebrated their happiest moments there,” Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway said.

Since its celebrated opening on July 18, 1997, the center’s revenues have never covered expenses, as predicted from the beginning. It has required a city subsidy primarily from the hotel room tax, ranging from $1.8 million to $4.3 million annually.

Monona Terrace suffered during the pandemic, when conventions and conferences fell from 60 in 2019 to 23 in 2020 and 2021 combined, and the annual economic impact from those events plummeted from $33.3 million in 2019 to $3.4 million in 2020 before inching up to $5.9 million in 2021.

Marvin Williams, of Milwaukee, catches a bluegill as he fishes from the Capital City Trail outside Monona Terrace. The center’s retaining wall quickly became a hot fishing spot.

The center is again hosting myriad events, including free concerts on its rooftop, which offers prime views of Lake Monona and the state Capitol.

The city has scheduled a 25th anniversary party with free music, food and drink vendors, and a drone light show for Saturday.

Six-decade saga

The effort to create Monona Terrace is part of Madison’s lore, a six-decade saga to prove the city “could put two bricks together.”

In 1938, Wright produced plans for a “dream civic center” linking Lake Monona to the Capitol. The original plan included an auditorium, city hall, courthouse, jail cells, marina and rail depot.

Wright liked the shape of the Capitol dome, and used it as design connection between the two buildings, said Heather Sabin, the center’s tourism coordinator. But he also wanted it to feel different from the Capitol and envisioned Monona Terrace on a lower scale, she said.

The project became a bitter political issue. Wright designed the building eight times, the last in 1959, just two months before his death. It inspired multiple referendums and court cases, and passage of a special state law in 1957 banning construction of any lakeside building taller than 20 feet that was repealed two years later.

Stairs in a rotunda lead visitors between three levels of Monona Terrace. The Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired design employs circles throughout the structure.

“The big idea nor the project would go away,” said George Austin, then the city’s former director of Planning, Community and Economic Development and later a consultant who helped shape many of the city’s biggest projects, including the $205 million Overture Center.

Early on, the biggest challenges were competing visions for the lakeshore site — development vs. green space — the unusual design, and Wright’s controversial personality.

In July 1990, then-Mayor Paul Soglin launched a campaign to build the center based on Wright’s design in an effort to revitalize a Downtown drained of bustle after the openings of the East Towne and West Towne malls.

There was a groundswell of support, and Taliesin Architects, Wright’s successor firm, confirmed the feasibility of the project. But there were concerns about the building’s impact on the lake and persuading the public of the need and financing.

The challenge, Soglin said, was getting city conservatives to “recognize the brilliance of Wright’s plan and get over their personal and political objections to the architect.”

Soglin, the city’s longest-serving mayor, appointed a large, diverse citizens commission that included critics of the project and Wright, some of whom became supporters. “In the 1990s, there were political activists who were more interested in their city than in their own sandbox,” he said.

The city, county and state under the leadership of then-Gov. Tommy Thompson, and the private sector led by businessman George Nelson, united behind the project. Madison voters approved referendum questions to approve the project and borrowing for it in November 1992.

Anthony Puttnam, a Wright apprentice and chief architect of the project as a member of Taliesin Architects, followed Wright’s final design to produce the iconic exterior. But he brought new elements to the interior because Wright was designing an auditorium and Puttnam a convention center.

To finance the project, the city contributed $29.3 million, the county $12 million, the state $18.1 million and the private sector $8 million, including activist Mary Lang Sollinger’s rooftop tile campaign that raised $1 million for enhancements. The debt on the building is now retired.

On July 18, 1997, the building opened to great fanfare and raves despite a style furor over the famously loud, 45,000-square-foot burnt-orange carpet. In 2014, the city replaced it with one featuring a burgundy background and less intense design as part of larger renovation project.

Thousands of onlookers crowded the walkways of Monona Terrace to watch the grand opening in 1997.

Despite pans of the original color explosion, the center’s gift shop sold $10,000 worth of remnants when it was replaced.

Environmental concerns faded. The building has achieved coveted LEED Platinum status for sustainability practices and a separate certification for comprehensive infectious disease protocols. Its retaining wall attracts a diverse group of anglers every day during the warmer months.

“I’ve been coming here for years,” said Donald Brown of Milwaukee, who returns three or four times a month, sometimes with friends or family. “People call it ‘the wall.’ It has the reputation of catching good-size bluegill and crappies. It’s good fishing here in Madison.”

In 25 years, the center has hosted an array of community events, and efforts continue to diversify its staff and board of directors.

Dane Dances!, a nonprofit formed in 1999, has provided free music, dance, and activities on late summer Friday nights on the center’s rooftop that routinely draws perhaps the most diverse social gatherings in the region.

Ken Lonnquist, right, with Liam McCarty on percussion, performs on the Monona Terrace rooftop for Lakeside Kids, one of many performances on the rooftop overlooking Lake Monona.

Monona Terrace “has always strived to meet the moniker of being a community center first,” said Downtown Ald. Mike Verveer, 4th District, who has been on the center’s board since its inception. But “we can always do better in every regard.”

More recently, the center’s Tony Gomez-Phillips has been shifting the center’s gardens to prairie-inspired planting that connects Wright’s architecture with a garden style that embodies his views of nature and how it interacts with people.

Monona Terrace to celebrate as it often does in summer: On the rooftop

The ripple effects and city growth since Monona Terrace’s opening are staggering.

In 1995, in anticipation of construction, the city created a tax incremental financing (TIF) district in the area to help pay for the center, deliver public infrastructure and invest in private development. The district opened with a base property value of $38.6 million, spent and repaid $67 million on projects, and closed with a value of $236 million this year. The much higher value property is now fully on the tax rolls.

Connie Thompson, hired to work at the center a month before it opened and named its executive director in February 2020, said Monona Terrace has made an impact, even if at first it was overwhelmed.

Convention attendees gather in the Grand Terrace of Monona Terrace.

Soon, there were restaurants popping up, condo projects being built, businesses returning Downtown, Thompson said. “I feel like we were sort of the catalyst,” she said.

The assessed value of commercial property in central Downtown nearly doubled from $612 million to $1.03 billion from Jan. 1, 1997, to 2002, city assessor’s records show. In the next 20 years, it quadrupled to $4.2 billion by 2022.

“Our numbers will naturally bounce around within a range, but the baseline of business and economic impact remains at very successful levels for a facility the size of Monona Terrace in a market the size of Madison,” said Bill Zeinemann, associate director for marketing and event services.

The cream-colored, $29.5 million, 240-room Madison Hilton, attached to the center and opened in 2001, is a direct result of Monona Terrace. It’s also a main catalyst for the multi-piece, $175 million Judge Doyle Square project rising between the center and Capitol Square, which includes a nine-story, 260-room hotel with a block of rooms dedicated to the community and convention center.

In 1997, the city’s hotel room tax generated $5 million with the sum increasing to $18.9 million before the pandemic in 2019. It dropped to $5.8 million in 2020 but rebounded to $12.1 million in 2021 and is expected to exceed pre-pandemic levels in 2023 or 2024.

Visitors to the rooftop gardens at Monona Terrace share a panoramic view of Lake Monona.

“One cannot overstate the importance of Monona Terrace to the vibrancy, vitality and economic health of Downtown Madison,” said Jason Ilstrup, president of Downtown Madison Inc.

“Maybe even more important than the economic impact is the impact such an event can have on the psyche of the city and its people,” Austin said. “To have accomplished such an epic project was a shot in the arm of the city, and I think it’s safe to say, as one example, that there wouldn’t have been an Overture Center for the Arts.”

More to come

Despite its panache, Monona Terrace has constraints.

The 62,830-square-foot facility is modest in size compared with its competition and should be expanded by 42,250 square feet to 105,080 square feet, HVS Convention, Sports & Entertainment Facilities Consulting, of Chicago, said in a February 2021 study.

Meanwhile, there’s increased competition all over the state and country, including new or expanded facilities, wedding barns and other event spaces, Zeinemann said.

The HVS study was commissioned before the pandemic, and city officials say any push for an expansion would come after recovery, when the community has dealt with basics and challenges such as unemployment and housing security.

Monona Terrace has helped define Madison’s skyline for 25 years.

But if and when it’s time, an expansion could bring more use, visitors, spending, jobs and tax revenue, HVS says.

An expansion, combined with the construction of the new hotel that’s part of Judge Doyle Square and other hotel space, would deliver a net spending impact of $32.7 million annually and 290 full-time jobs for the city, plus $23.1 million annually and 200 jobs for the state, the study said. The improvements could generate $481,000 in annual hotel room taxes for the city and $1.6 million in annual tax revenue for the state.

“If Monona Terrace had more space, we’d be able to book conventions with a larger attendee base,” said Ellie Westman Chin, president and CEO of Destination Madison. “We’d also be able to book more sporting events into the venue. Finally, we’d be able to book more concurrent events.”

A more recent study sees a focus on attracting larger events, more of them, and getting them to book further in advance, Zeinemann said.

A potential expansion of Monona Terrace is being considered as part of the redevelopment of the Lake Monona waterfront and continued improvements to Law Park and parts of John Nolen Drive.

Recently, an array of firms that have designed some of the most celebrated public spaces in the world have joined a competition to reimagine the popular but uninspired waterfront between Williamson Street and Olin Park. A 13-member ad hoc committee is expected to select three finalists by the end of July and recommend a preferred master plan by Sept. 1, 2023.

Key for Mickey 8 30 97

1997: Mayor Sue Bauman gets another earful, but this time from Walt Disney luminaries Mickey and Minnie Mouse. On the Monona Terrace rooftop Friday, Bauman hands the mice a key to the city carved from a 40-pound block of aged cheddar. In town this weekend as guests of TCI Cablevision of Wisconsin, Mickey and Minnie will also visit sick children in Madison hospitals.

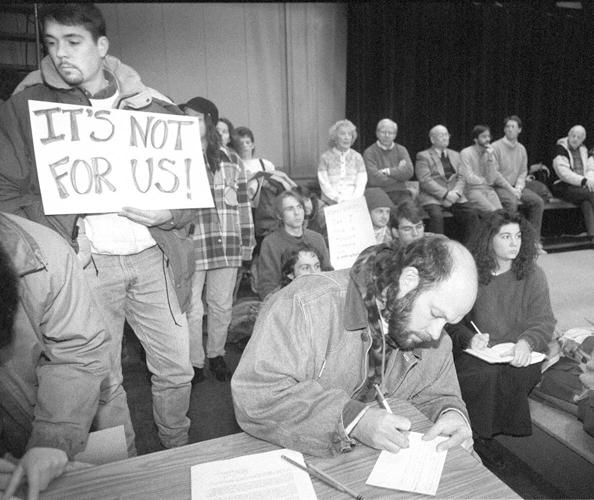

Monona Terrace carpet 7 17 97

1997: Tony Putnam, principal architect for the convention center, believes visitors to Monona Terrace will appreciate the carpet in the winter when Lake Monona is frozen and the bright orange floor lends warmth to the cold Wisconsin winter. For now, it’s getting a chilly reception.

Cheese unpacked 3 21 00

2000: It was like Christmas morning for cheese lovers at Monona Terrace on Monday as hundreds of cheeses were unwrapped, labeled for competition and repackaged. Chief Judge Bill Schlinsog, right, unpacks an Austrian cheese with volunteers Dick Groves, left, Madison, and John Jacobs, Antigo, center.